The US insurance industry doesn't want to carry pandemic risk after seeing the impact of Covid-19, but the choice could lead it into obsolescence

Two major US insurance associations say pandemics are 'uninsurable' (Credit: PixaBay/Alexandra_Koch)

The US economy, like those of many other countries around the world, was blindsided by Covid-19. In an effort to ensure the damage wrought by the global pandemic can never befall the country again, members of the government and the insurance industry have put forth their plans to manage future risk. Peter Littlejohns examines why the choice could have long-lasting consequences for insurance as we know it.

“Pandemics simply are not insurable risks.” These words, uttered by Charles Chamness, president and CEO of the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies (NAMIC), sent a strong message that US insurers won’t carry the risk of a pandemic on their books.

Of course, the industry’s reaction to the current situation revealed that this has always been its position, even though a looming wave of litigation may yet prove policies were never airtight enough to enforce it.

A government backstop for pandemics was touted in the US in March, when the extent of the Covid-19 threat was realised through shutdown and stay-at-home orders issued across the globe.

Some within the insurance industry expected the arrival of legislation outlining such a plan to be a welcome measure that could prevent the supply of business interruption (BI) coverage from drying up.

Former New York state insurance commissioner Howard Mills recently drew comparisons between now and the BI coverage market after 9/11 to show how a government backstop for losses in the form of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) made an otherwise uninsurable risk insurable, and by extension stopped parties along the risk-transfer chain from losing their appetite.

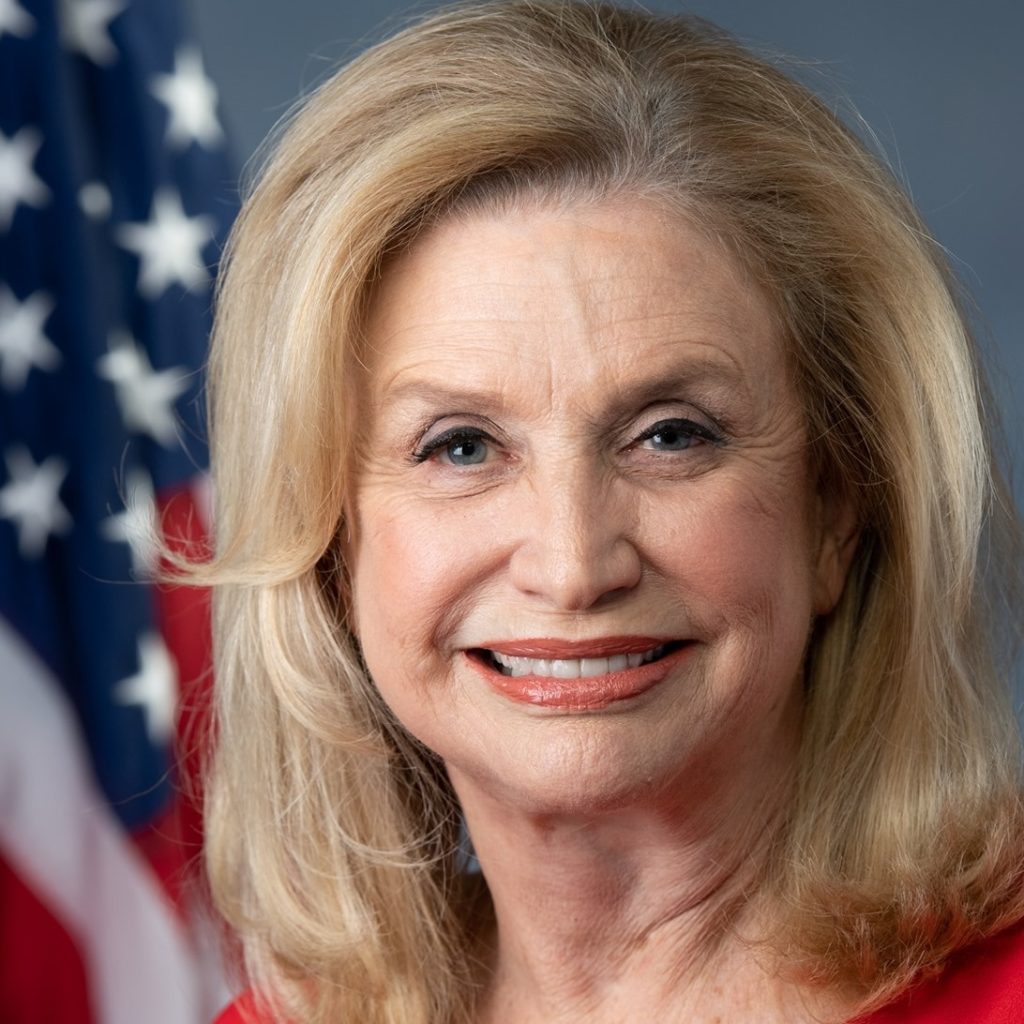

On May 26, New York representative Carolyn B Maloney introduced bill H.R.7011 to the House of Representatives drawing the same comparison and arguing that the Pandemic Risk Insurance Act (PRIA) it would create will replicate the success of TRIA.

But rather than supporting the bill, much of the insurance industry has taken a position of abject refusal – a move that has baffled some and reignited the debate about whether pandemic risk is, by its very nature, uninsurable.

Widespread, severe and unpredictable

“They [pandemics] are too widespread, too severe, and too unpredictable for the insurance industry to underwrite” – those were the comments from Chamness as his organisation led the charge against the PRIA with its own alternative scheme, the Business Continuity Protection Program (BCPP), which would shift the entire cost burden of future pandemics onto the US government.

But while NAMIC and fellow industry association APCIA (American Property Casualty Insurance Association) – which when combined claim to represent more than 90% of the industry – have come out with the strongest condemnation of the PRIA, not all of their peers in the industry agree with the stance.

Marsh and McLennan Companies (MMC), as well as the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) – a non-profit advocacy group for global risk management professionals – have backed the bill.

Agreeing pandemic risk is insurable could weaken insurance firms’ legal defences

Some industry observers believe there’s a strategic reason for the steadfast refusal of NAMIC and APCIA to cover pandemics, and it’s related to the equally stoic defence from insurers – many of whom are the organisation’s members – denying business interruption claims because pandemics aren’t covered by their policies.

Zachary Finn, risk management and insurance professor at Indiana’s Butler University, believes the industry is being pragmatic to ensure that legal professionals bringing cases in favour of firms with denied business interruption claims can’t take advantage of a soft position from the industry.

“The insurance industry has taken the position that pandemics are uninsurable in order to make it easier to defend their position that Covid-19 is uninsurable,” he said.

“They’re thinking ‘if you’re going to try and sue me in court and say I owe policyholders business interruption losses, I’m here to tell you I don’t owe them anything, because not only did they not have coverage, but pandemics are uninsurable’.

Questions have already arisen over whether coverage for the circumstances posed by Covid-19 exists, and many court decisions are expected to hinge on whether or not the policies in question included an exclusion for viruses.

“They’re almost being forced to take the position that pandemics aren’t insurable in general, in order to strengthen what I think is a weak hand,” adds Finn.

Aside from the potential legal motivation of the insurance market taking such a hardline stance, Finn says a continual failure to educate the distribution network that sells policies underwritten by insurers about what those policies cover has contributed to the current ambiguous legal situation.

“That’s the Achilles heel, they didn’t update [insurance] licence exams”, he says

“I have a former student who has an Illinois insurance licence. Illinois is one of the largest insurance centres in the US, and you would think their licence exams would be up to date and cutting edge, but he said they didn’t even mention pandemics.

“There’s a whole agency distribution network selling products that include a major deficiency… and they’re selling products they don’t understand because there’s a major exclusion that they were never trained to explain was there.”

Central banks may provide liquidity faster than insurance companies

Another expert in insurance risk who has been observing the passage of the PRIA and the introduction of its counter proposal, BCPP, is Jeffrey Sharer, JD, former vice-president of investment management company Goldman Sachs & Co.

Sharer’s role involved global oversight of hazard and insurance risk management for the whole of The Goldman Sachs Group, and for him, the operative question is as follows: “What is the best way to get resources and liquidity to the people impacted by a pandemic?

“Is it through the central banks and their facilities, or is it through insurance companies?

“On a historic basis, that liquidity from central banks is much faster than what you would get from an insurance recovery payment.”

It’d be easy to dismiss this argument when the Trump administration’s Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) has been widely criticised for its strategy to manage the economic impact of Covid-19.

Alongside interest rate adjustments and propagating favourable lending rates, the Federal Reserve had to implement the (up to) $1,200 payment to every American taxpayer, a fiscal choice that has been criticised as poorly targeted and wasteful.

But the BCPP takes the concept of insurance and replaces the role of private risk carriers with government institutions, so that when payments are made, they’re based on the actual losses of businesses.

This also means that unlike in a traditional insurance operation – in which claims would go through a process of loss adjustment – payments would be made based on an agreed-upon criteria and at a set value, an approach commonly known as “parametric insurance”.

Sharer also sees a role for the insurance industry in the process, not as a carrier, but using the technology and modelling capabilities currently transforming the way financial protection products operate.

One key example he gives is the machine-learning algorithms many rely on to stamp out fraudulent claims, which would allow the government to flag loss reports that don’t align with the income and tax profile of a business, and keep wastage to a minimum.

“If they [the insurance industry] don’t talk about what services can be provided, they’re really missing what insurance will look like in the future.

“You also wouldn’t have the National Flood Insurance Program or even the windstorm program in the US without all of the modelling capabilities of insurance companies.

“These are all things the government could utilise.”

How does the BCPP manage pandemic risk?

In practice, the BCPP would allow businesses to purchase revenue replacement, with basic coverage entitling them to receive 80% of their payroll expenses, and more costly options available to cover extras such as operating expenses and the cost of employee benefit programmes.

The plan is in its infancy, and its modelled on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), but rather than a risk-sharing framework with a backstop, the private insurance market wouldn’t pay anything to cover the losses.

Sharer doesn’t deny that NFIP has had its issues, after all the program has been delayed several times amid concerns over its funding and the efficacy of its risk-mapping procedure.

But when it comes to comparing the current iterations of the PRIA and the BCPP, it’s the latter he sees as being more likely to provide the speedy injection of liquidity businesses need.

This, he says, is because central banks are “more geared” to handle risks that include “cross-industry” exposure.

“A pandemic insurance programme modelled after the flood insurance programme is probably the best way [to insure pandemics] in terms of current structures,” he adds.

“Is it the best? no. Are there issues with it? Yes. But it’s a starting point.”

Is the BCPP more efficient than an insurance backstop for pandemic risk?

Differences between the BCPP and PRIA start with the assumption of each plan that pandemics are, or are not, insurable.

Finn, who had a career in risk management that included a five-year stint with food manufacturer The JM Smucker Company, before he decided to teach, believes the reality of corporate risk management flattens the argument that they aren’t.

“The reason larger businesses have pandemic insurance is that they deal with excess and surplus lines brokers, which have more training [than regular brokers] and deal with unique risks.

“These businesses know pandemics are insurable because they’ve been buying or declining the coverage for years.”

The cost of purchasing pandemic insurance, however, is prohibitively high, which is one element of creating resilience to future viral outbreaks many hope PRIA can solve.

In Congresswoman Maloney’s proposal, 95% of pandemic losses over the threshold of $250m would be covered by the government, but only after they’re paid upfront by participating insurance firms, which would then be recompensated.

According to Sharer, insurers aren’t keen on carrying the remaining 5% because they can’t predict in any meaningful way, given the rare and varied nature of pandemics, what cost it could incur on their balance sheets.

He also says the fact the event either happens, or does not, and affects everybody at once if it does, makes it impossible to analyse loss trends – a process insurers rely on to predict future losses, adjust their risk appetite and reserve capital appropriately.

But Finn argues spreading risk across policyholders is just one way of managing exposure.

“There are three ways to spread risk: Across policyholders, across time and across exposures,” he says.

“The BCPP spreads it across policyholders, backstopped by the federal government, with the benefit of time as well because we’re unlikely to have another pandemic for a while.

“But it doesn’t spread it across exposures, which makes it immediately less efficient than anything that does.”

This matters, according to Finn, because the corporate risk managers he points to as having been able to buy pandemic insurance for years could choose to pool the risk with other perils in a captive insurer so it’s spread across exposures too, an approach he argues would be cheaper than the BCPP.

“The Fortune 500 will not want BCPP, because their exposure is so large that their cost would be enormous relative to the kind of programme they could create themselves by taking pandemic risk and pooling it with other risks,” he adds.

It’s not just the corporate level that Finn advocates a bundled approach to certain risks either – he would like to see a similar scheme at the federal level to make catastrophes more manageable.

“We should move to a system of basic perils, broad perils, and then government-backed catastrophic perils.

“Take pandemics, terrorism, flood, cyber… package it all up into one public and private partnership backstop – that will create a soft mandate for all of it.

“If you’re an exposed coastal property in South Carolina, you’ve got to have national flood insurance.

“If you’re a New York skyscraper next to the freedom tower, you need TRIA.

“If both are now combined, the South Carolina company can’t get their flood insurance without putting a nickel in for terrorism, and the folks in New York having to buy terrorism insurance have to kick in for floods.”

Could ‘Big Tech’ help companies cut out the insurance industry completely?

One prediction from Finn that would be particularly dystopian for the insurance market is that, in lieu of traditional insurance capacity for what are seen as uninsurable catastrophes, players outside of the industry will take up the opportunity to collect premiums instead, and not just for unlikely catastrophes like pandemics.

“Another talking point that NAMIC has is that there’s not going to be high enough subscription to create the necessary pooling effect for PRIA to work,” he says.

“But that’s because they’re not thinking about all of the ways to spread risk.

“Well, they’re not the only people that are able to underwrite risk.”

It’s Big Tech companies, like Amazon, Finn believes are well-placed to take the initiative, due to the amount of capital they have and the ability to build and launch technology to manage the portfolio of risk.

Of course, there would be a lack of knowledge about how to pool it, but he adds that brokers will be more than happy to help.

“The more the insurance industry digs in, the more insureds get mad, and the more it puts brokers in the middle, and brokers are going to be forced to take a side.

“Agents and brokers understand how to manage and pool risk.

“If a company like Amazon wants to set up an insurance company, it needs that expertise more than ever.

“If anything, they [agents and brokers] will make more money enabling this disruption than they would helping to preserve the status quo.”

With these experts in risk at their disposal, Finn believes Amazon could leverage their existing advantages to move into the personal lines market too.

He says: “Auto manufacturers could start to sell insurance to their drivers, or Amazon could say ‘if we’ve got an Alexa in every home, or smoke detectors and other sensors, why couldn’t we start selling homeowners insurance?’

“And when they’ve sold all of that homeowner’s insurance and got this huge portfolio of risk, they can start selling pandemic insurance, or cyber insurance, or any other billion-dollar line of coverage.

“They can then securitise it and lay it off on Wall Street as insurance-linked securities.”

Amazon’s Echo device – frequently referred to as Alexa – contains a feature called Alexa Guard, which can detect the sound of smoke alarms, carbon monoxide alarms, or glass breaking and notify homeowners absent from their property.

The insurance industry has already seen partnerships between technologists and risk carriers to add an aspect of risk management to homeowners’ policies, but Finn believes Amazon could issue policies itself far cheaper than incumbents.

For Big Tech companies, the cost of serving a policy could be cut dramatically, because they wouldn’t need to pay for advertising or distributor commissions, as they’d already have traffic on their sites, and they could set up an in-house end-to-end insurance platform.

“By saying pandemics are uninsurable, insurance companies are forcing us all to do that math, but they don’t want us to, because the answer to that problem is that they don’t need to exist anymore,” adds Finn.

Does the PRIA need amending?

Finn’s critique of BCPP does not mean he sees PRIA as being without flaws.

He contrasts the bill’s approach to insurance companies with the “sweetheart deal” given to banks participating in the Trump administration’s Paycheck Protection Program, which receive up to 5% of the value of every loan they process as an administration fee.

With the PRIA, insurance companies would pay 5% of their gross earned premium for the most recent tax year as an excess before the government backstop takes over.

Finn says: “Why should banking get a sweetheart deal and then the insurance industry agrees to a backstop that screws them?

“The government should probably backstop PRIA 100% in year one, with an agreed future risk-share percentage and a runway to allow insurers to build up capacity.

“Anything should be negotiable.”

Which plan will prevail in congress?

Although BCPP satisfies Sharer’s main concern of quick liquidity based on loss, with PRIA in its first iteration and the likelihood of multiple amendments high, he’s open to the possibility his opinion could change.

One area he stresses isn’t being paid enough attention is the role that lenders played in driving the TRIA post 9/11, something he believes will play a key role in shaping pandemic insurance at the regulatory and private market levels.

“The question is whether companies are really willing to pay for it.

“If you don’t have lenders and rating agencies saying [pandemics] must be insured for, there’s no rationale to spend the money for it.

“If there’s really no requirement to be insured for it, why are they going to incur that expense?”

Finn believes companies that do choose to cover themselves are more likely to do so through a captive insurer.

But the larger issue, he believes, is that the US needs to know how much risk it created in other areas of life by shutting down in the way it did – the answer to which will solve the question on the insurability of pandemics.

This is especially true, he argues, when some things are “worth dying for”, like the current fight for racial justice sparked by the death of George Floyd, or a low-income single-parent needing to work regardless of Covid-19 in order to feed their kids.

“This is a national referendum on risk tolerance,” he says.

“Would we ever shut down nationally again? can anybody quantify the threshold at which that would happen?

“If the answer is that we will never shut down again… all of a sudden pandemics are one of the most insurable risks out there.”