Driverless car technology is evolving fast, with some believing full autonomy could be available by 2030 - and while it will make vehicles safer, the jury is out on how it will affect the insurance industry

An autonomous vehicle demonstration from Waymo (YouTube/ Waymo)

Nobody quite knows at exactly what rate automation will extend to our roads, with fast-developing driverless car technology still not at a level at which drivers can fall asleep at the wheel. What is clear, though, is that the insurance industry will have to adapt to cover a new set of risks, as Peter Littlejohns reports.

The year is 2040 and two cars collide on a busy motorway.

There’s nobody injured, but the occupants are visibly shaken as they climb outside to assess the damage.

Usually, this would be the time they exchange insurance details and begin the laborious process of finding out who takes the blame — but neither approach.

This is because motor insurance is a thing of the past, no longer necessary when driverless cars have eliminated the human error responsible for 95% of road accidents.

But is the risk really gone?

Not for Darius Kumana, chief product officer of insurtech start-up Wrisk, who doesn’t believe the insurance sector has anything to worry about just yet.

“There are always going to be perils — it’s just going to be a question of who is liable, and when,” he says.

“You can have all of the technology in the world, and it’s not going to stop somebody from running a key down the side of your car.

“If insurers need to pay a claim to replace the bumper, for example, you’re not talking about a £50 piece of plastic — you’re suddenly talking about thousands of pounds of electronics because it’s loaded with sensors.”

And it’s not just the age-old risks of vandalism and parts breaking down at inopportune moments, but the new concerns attached to cyber vulnerabilities for connected and autonomous vehicles as the automotive industry marches on with the vision of getting them on the roads.

Matthew Avery, head of research at insurer-funded market investigator Thatcham Research, agrees it’s unlikely the motor insurance sector will diminish — simply because when repairs do need to be made on driverless cars, they’ll be much more expensive.

“Driverless cars should reduce insurance risk, but may not have a big effect on premiums because you’ve got the repair costs associated with all of these sensors,” he adds.

“These vehicles are by their very nature complicated so you are unlikely to see a big change in the market.”

While neither Avery nor Kumana believe motor coverage is going anywhere, both are certain autonomous vehicles are coming and that they’ll have a dramatic impact on the insurance industry.

A utopian vision of driverless cars

A self-proclaimed futurist, Kumana is one of many who takes a glass-half-full approach to the prospect of autonomous vehicles, believing they could be on the road at scale in developed nations such as the UK within 10 years.

“This will happen faster than people give it credit for,” he says.

“With every car manufacturer I’ve spoken to, and we’re talking to firms like BMW, Jaguar Land Rover and Volvo, everybody is having that conversation.

“They may have different views about when it will become a mainstream reality and 50% of their cars will be offered that way — but they’re all talking about it and they can all see the potential.”

Along with Wrisk co-founder and executive chairman Niall Barton, Kumana is betting on the concept of vehicle ownership decreasing with increased autonomy, suggesting alternatives such as a Netflix-like subscription where vehicles become more of a service than an asset.

Companies such as Zipcar, Getaround and VW’S WeShare are already exploring this space with current technology.

But Kumana doesn’t believe people will stop owning vehicles for pleasure, just that doing so will be seen on the fringes of society, while the majority rely on a vehicle-as-a-service type of arrangement.

He admittedly likes to “future gaze” quite far ahead, describing a utopian ecosystem in which “getting from A to B is something looked after by society”, and driverless cars simply an enabling tool.

“They’d operate like a swarm, being free at the point of need, with consumers not needing to pay because they’re captive customers in a little bubble, where they can be plied with advertising,” he says.

“The vehicles can then drive themselves to get a recharge with the revenue they create, or to a mechanic to get fixed up.”

In some instances, the wear and tear on one of these self-sovereign vehicles may be too much, but Kumana’s utopian vision has a solution for this too.

“It can drive to the recycling place and decommission itself,” he adds.

Door-to-door driverless car service by 2030?

Others are more reserved in their foresight, like Matthew Avery.

The director of research at UK not-for-profit Thatcham Research, an organisation funded by insurers to carry out motor industry research, believes the 10-year prediction from Kumana is ambitious.

“The automation level where a driver can totally nod off or do something else is likely to be available beyond 2025,” he says.

“Still, that will be within a certain location — what we call geofenced.

“The car will know where it is and automation will only be allowed within that particular area.

“But door-to-door automation won’t be available until 2030 and beyond, because it requires a massive amount of mapping to be done around all of the errors and streets to make sure the systems are competent enough.”

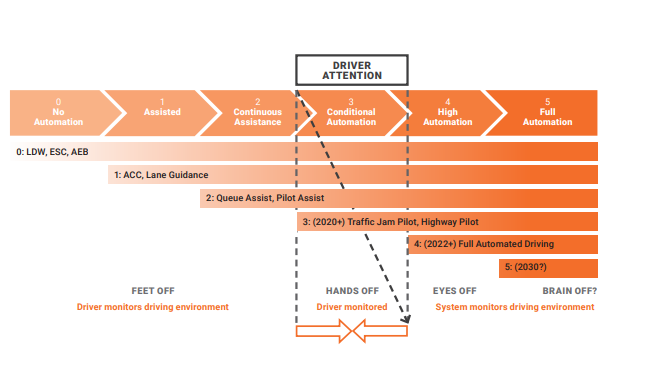

Autonomous driving is rated on a “sliding scale”, where level zero is no automation and level 5 is “full automation” — the door-to-door scenario Avery describes.

Right now, he says manufacturers are progressing through level 3, with level 4 being the scenario he describes as being beyond 2025.

Level 4 involves full autonomy, but with a driver sitting ready to take control if needed, while level 5 requires no driver input at all.

How will driverless car technology change the insurance market?

The shift in liability could mean OEMs offer insurance themselves

As the question of who’s to blame for a crash puts more pressure on the company that produced the technology at fault, Avery says original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) might make insurance a part of their businesses — especially as they become more service-oriented.

“The challenge to insurers is that once the vehicle manufacturers are on the hook for these systems if they go wrong, they’re going to start providing insurance.

“They may not provide it themselves, because they’re probably not capitalised enough to do that, but they might start working with reinsurers in the market.

“You’re going to get this sort of consolidation with the insurance market, so consumers don’t go to a comparison site or direct to an insurer to buy coverage.

“Instead, it’s there, built into the cost of the vehicle, when you use it.”

Avery doesn’t believe personal car sales will disappear, as OEMs begin to provide mobility-as-a-service rather than just as a product, but rather that they’ll form a separate business model within each company.

He says: “We will definitely see the market diversify, but manufacturers get most of their money from private car sales, not leasing, so they’re going to want to retain that market.”

The level of diversification, he believes, will depend on the different areas served by OEMs, and how much need there is for a personal vehicle.

Using the example of a large, heavily-congested city like London, where car ownership is less attractive, a mobility-as-a-service offering may influence their buying decisions.

“What we see happening is not a root-and-branch change, but just new ways of doing things,” Avery adds.

Driverless car technology presents an opportunity for insurtechs to provide insurance

Kumana sees this shift in liability as an opportunity for insurtech companies, giving them a chance to develop products that suit the service-based business models he expects to develop as cars become more autonomous.

As with the majority of industries, the key to progress for insurance will be data.

“OEMs are sitting on vast swathes of information that they almost don’t know what to do with, or how to monetise or yield benefit from,” Kumana says.

At the same time, he believes insurers can see the benefit of using that data, but because their businesses are optimised for “efficiency” rather than “innovation”, incumbent players aren’t well-placed to capitalise on the opportunity the way insurtechs are.

“They are changing their approaches, but it’s like they’re walking through treacle,” says Kumana.

He explains that for an established insurer to change its systems in a way that protects an existing book of business — while also “flipping customers onto a subscription model” ranking them on new, data-driven ratings factors — would be impossible.

“They see start-ups that have created a legacy-free ecosystem as a way to play in that space without having to deal with this problem,” he adds.

As driverless car technology develops, more of this data will be collected from OEMs, making a key part of Wrisk’s future business partnerships that can integrate their data streams into risk-rating algorithms.

“Vehicle manufacturers know best how their technology works and, based on their data, how it impacts risk — whereas insurers tend to use quite blunt instruments to assess it,” Kumana explains.

Regulatory challenges

Avery says the wider insurance industry has an immediate concern over what can be classified as autonomous, pointing towards a definition he expects to be released in 2021 by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe to highlight the issue.

He says: “In this document’s rules, a vehicle can only stop on a road lane, which we and the insurers see as a fundamental safety issue because if you’ve nodded off and your vehicle stops, it will just be exposed to all the traffic.

“We’re advocating that in this UN standard, a vehicle must move out of a lane to find safe harbour.

“That’s not currently accommodated for in the proposed regulation, and insurers are not comfortable with that.”

If the UN decides to go ahead with this, he says that insurers are likely to reflect what they see as increased risk through a jump in premiums.

“Any vehicle that is classed as being automated will go onto a list, and insurers will have to cover it as an automated vehicle whether they like it or not.

“But of course, insurers are empowered to price it accordingly, so if they see it as high risk then there could be a high premium.”

A second area Avery sees as a potential issue is proving who was in control of the vehicle at the time of a collision — the driver or the automated system.

To solve this, he says there needs to be a verifiable source of data shared by OEMs to insurers, something he and Thatcham are enabling by setting standards for testing alongside the European New Car Assessment Programme.

Once those standards are set in stone and insurers can rely on OEM data to validate liability in an accident, Kumana says Wrisk is ready to integrate the process of defining who is in charge of the vehicle into its system.

“We already have a platform that is capable of making an instant change to the rating, capacity or policy documents.

“We’re just waiting on the manufacturers to give us the triggers.”

Bringing driverless cars to our roads will be a messy business

Both Avery and Kumana agree that the evolution of driverless car technology, as well as the insurance risks it presents, will not be a smooth process.

“It’s really easy to show a driverless car is convenient, but all it takes is one accident to set people back three years in terms of their trust,” says Kumana.

“It will be messy, but innovation is always messy.”

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents’ statistic on 95% of road accidents being blamed on “human error” suggests autonomous vehicles could reduce crashes dramatically.

Avery is concerned that the longer regulatory bodies take to decide what’s safe, the more unnecessary casualties that will happen.

“There’s a tipping point, and nobody quite knows where that is, which asks exactly ‘how safe is safe enough?'” he adds.

The public perception of autonomous vehicles creates another barrier to adoption, something that could be worsened when they crash.

“Under certain fairly extreme circumstances, there will be accidents, there will be injuries, there may even be fatalities — but what matters is that we learn from them and understand what’s gone wrong, ” he adds.

Age has an impact on who’s comfortable to travel driverless

It won’t come as a surprise that younger people are more eager than their older peers to adopt driverless cars.

A recent survey from the Institute of Mechanical Engineers found two-thirds of people are uncomfortable with the idea of travelling in a driverless car.

But a deeper look into the stats shows 42% of 18 to 24-year-olds are happy to be an occupant in a driverless car, while only 11% of over-75s said the same.

Hoping that public attitudes shift, Kumana sums up the way the world reacts to new technology with a quote from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams:

“Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary, and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

“Anything that’s invented between when you’re 15 and 35 is new and exciting, and revolutionary, and you can probably get a career in it.

“Anything invented after you’re 35 is against the natural order of things.”