Sharin recently received €1m ($1.1m) in funding to support its vision for providing "microinsurance" to the sharing economy and reducing CO2 emissions in the process

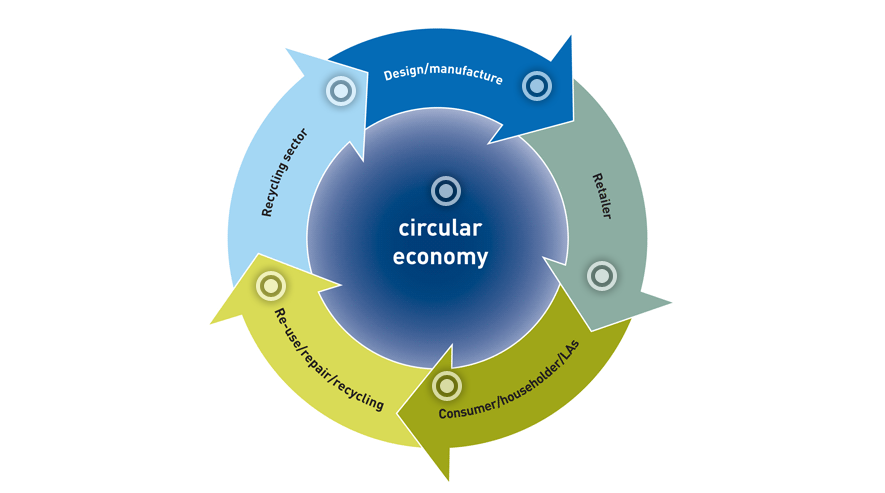

The circular economy promotes reuse in place of manufacturing more of something

Circular economies are mostly promoted by earth-conscious organisations looking to reduce the environmental impact of waste – but insurance could play a key role in sustainable consumption in the future. Ola Lowden, CEO of Swedish insurtech Sharin, tells Peter Littlejohns how it plans to reduce harmful emissions and promote circular business models by insuring sharing platforms

The impact of climate change and recent international push to reduce waste consumption is a top-of-mind concern right now, with many suggesting we move towards adopting a circular economy to avert the dangers associated.

But Swedish insurtech start-up Sharin wants to apply the same concept to the sharing economy, and aims to do this by providing insurance to cover lenders and borrowers.

The driving belief is that customers would be more inclined to use sharing platforms – which adopt peer-to-peer business models that enable people to access services through short-term rentals for much cheaper than buying them – if they knew they had protection in place should something go wrong.

The idea Sharin puts forward to implement this protection is microinsurance – a type of cover calculated based on each individual use of an item or property – rather than an annualised premium.

CEO Ola Lowden says: “The sharing economy market is growing and we believe it is the future of how transactions will be done.

“The peer-to-peer lending segment is a lot bigger than just Airbnb and Uber, and a lot of companies are trying to apply circular models into their value chain.

“But when they do so, they go from a system based on ownership to one based on renting or leasing products, and if the insurance system continues to be based on ownership then the risk models aren’t going to add up.

“When products are sold as a service, rather than sold as a thing, you need an insurance model for that service – and we think microinsurance is a better way to do that.

What is Sharin? Explaining its insurance model

Sharin is a Stockholm-based insurtech focused on providing microinsurance to the sharing economy in Sweden.

It was founded in 2017 by Ola and his friend and colleague Emanuel Badehi Kullander – who serves as chairman of the start-up.

The two worked together at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs during Ola’s eight-year career as an expert on trade and the circular economy for the Swedish government.

As well as working on regulatory issues in foreign trade, Ola spent a short time in the country’s Ministry of Finance.

He says: “I’ve never worked in insurance at all, I was working as a lawyer in the Swedish government. I was an expert on trade and development issues associated with it.

“When I was working as an appointed expert on the sharing economy and the circular economy at the Ministry of Finance, we were looking into the consumer aspect in relation to both, and the government was worried about how insurance covers them.

“I was set the task of convincing insurance companies that they had to do something about this – but after three months of trying to do so and realising they didn’t want to, we decided if they didn’t, then we would.”

This month, Sharin – which is named after the deliberately mispronounced expression “sharin’ is carin’” – received $1.1m in seed funding led by early-stage venture capital firms Inventure and Luminar.

Insuring lenders and borrowers

Traditional insurance models are calculated, usually on the basis of an annual premium, using large amounts of data from previous claims to create a price for consumers.

In his governmental role, Ola found the biggest reason insurers didn’t want to adopt a microinsurance model was that the sharing economy wasn’t big enough to necessitate a change in their business.

“The problem for them is that they have a lot of data, going back 100 years in some cases, and if they had to assess risk on a per-use basis,” he says.

“They don’t have the data on the person borrowing the item, so they can’t calculate the risk, despite the fact the person who could break the item is the one posing it.”

After consulting with almost all of Sweden’s sharing platforms, which Ola already had ties with from his time working in government, he found they were most concerned about customer churn on the supply side of the business and “desperate” to get more people renting their stuff, something both decided insurance would be a big part of.

In order to solve this issue and come up with a new framework, Sharin enlisted the help of the duo’s friend, Dr Filip Lindskog, a professor of insurance mathematics at Stockholm University.

Ola says: “We took all of the transaction data from the platforms and took it to Filip and he created a new risk-handling model based on scenarios experienced by them.

“We created an algorithm from that model that we can put directly into each platform’s API and it calculates microinsurance policies for each transaction.

“Every time we get a new platform on board with a new risk to insure, we take the data to him and he updates the model.

“We have a huge queue of platforms that want to sign up but currently there’s only five of us, so we don’t have time for everyone.”

How sharing economy could help reduce emissions

According to Sustainable Governance Indicators – a cross-national survey to determine the efforts made by countries within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to solve environmental issues – Sweden is the top country in the world in the effectiveness of its environment policy.

But Sharin hopes to push its reputation even further by expanding the role the sharing economy has on day-to-day life in Sweden, believing it will protect the environment from further damage.

He says: “The main ambition is to drive down CO2 emissions because having ownership of things isn’t a very efficient way to use them.

“If you produce a car and it’s only used 50% of the time, and a lot of people are doing the same thing, the production emissions are really high – even with electric cars.

“If we can use the sharing economy to increase the usage of each car, or any other item, we can reduce the production of each of them and in turn reduce the CO2 emissions released in making them.”