Several veterans in the captive insurance industry see the potential for explosive growth in this hard market, spurred on by the pandemic, which could result in the loss of commercial insurance premium forever

Experts expect the current hard market to carry on for a matter of years due to Covid-19 (Credit: PixaBay)

The captive insurance sector tends to benefit from a hard market. As the price of traditional insurance grows, so too does the prospect of businesses opting to carry more of their own risk until the market softens for buyers. A captive is one way firms can do this, but alternative risk transfer can offer more than just cost benefits. Peter Littlejohns explores why captive insurance is growing in popularity, and how this could lead to insurers losing commercial market share.

The worst hard market the insurance industry ever experienced was that of the 1980s, when for reasons still debated by industry academics, the capacity to cover commercial liability risks reduced significantly, causing prices to leap and businesses to look at captives as an alternative way to address their insurance needs.

One oft-cited statistic that drives home just how hard that market was is that during the period from 1984 to 1987 premiums for general liability coverage increased from about $6.5bn to approximately $19.5bn.

There have been periods of hardening since, triggered by hurricanes during the 1990s and the 9/11 terrorist attack.

But there’s been a general acceptance that a better understanding of risk – driven by advances in technology and the ability to predict outcomes – has allowed the industry to avoid knee-jerk reactions to loss events.

In their 2009 book Catastrophe Risk Financing in Developing Countries: Principles for Public Intervention, authors J. David Cummins and Olivier Mahul note the following:

“The market has functioned well in response to losses from mega-catastrophes, and evidence… shows that the market’s ability to sustain catastrophic losses and to recover quickly from catastrophic events has improved significantly since the 1990s. Thus, the cycle may have moderated somewhat, at least in respect to mega-catastrophes.”

In a 2011 interview with Business Insurance, the president of reinsurance brokerage EWI Re Steven M. McElhiney went one step further and called the hard market of the 1980s a “once-in-a-generation event”, predicting that the insurance cycle would increase or decrease gradually “in the absence of a major catalyst”.

The current coronavirus pandemic could be that major catalyst, and just like in the 1980s, businesses are increasingly looking to captives as an alternative to a commercial insurance market that is pricing coverage out of their reach.

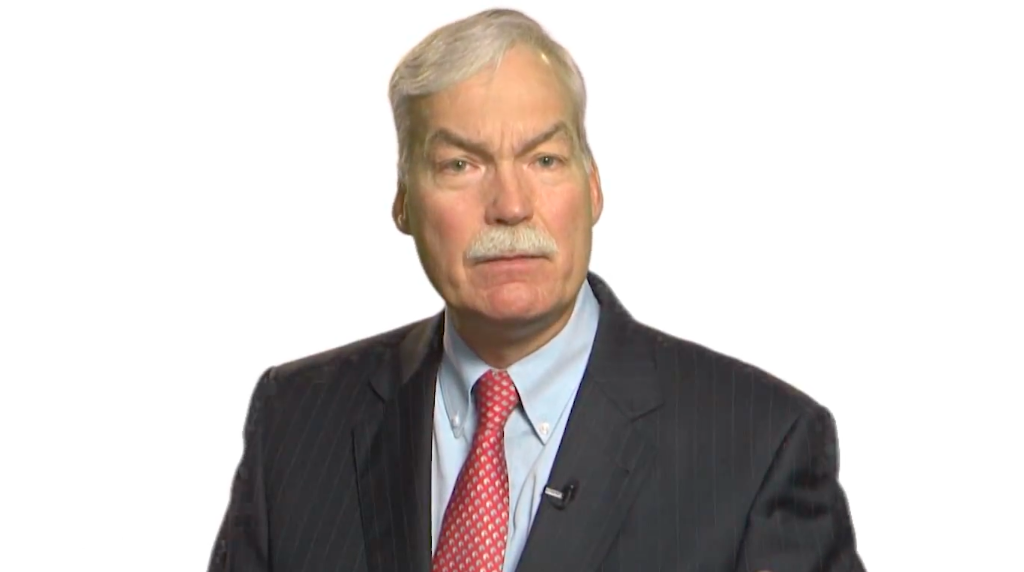

One veteran of the captive sector, Willis Towers Watson director of risk consulting Jim Swanke, definitely sees parallels between now and the hard market he worked through more than 30 years ago.

“You’d have to go all the way back to 1986 to find a time where many captives were being formed.

“Being in the business for 40 years, I can reflect on the duration of that time… and with the pandemic, a likely recession and current social unrest, this hard market is probably going to go at least another 24 to 36 months.

“Organisations are seeing that and they’re saying ‘how can I control my own destiny and insulate myself from the madness?’

“They’re doing it with captive insurance companies.”

In its latest survey, Business Insurance pegged the global captive count at 6,135 at the end of 2019 – Swanke expects this to increase dramatically in 2020.

“We’re setting them up as fast as we can get the studies done. During this hard market, I think there could be another couple of thousand.”

Why do industry experts see the hard market continuing for so long?

To understand why many expect the current hard market to persist for up to three years from now, it’s necessary to grasp what makes this situation different to that of the mid-1980s.

“It’s similar in the sense that both hard markets were preceded by a period of continuous rate cuts,” says M. Michael Zuckerman, associate professor of risk and insurance management at Temple University’s Fox School of Business.

“Where they’re different is in regards to the economic environment.

“What caused the market crash of the 1980s was the fact that insurance companies had enjoyed a period of time where interest rates were very high, and property and casualty insurers invested heavily into fixed-income instruments.

“They were making a lot of money from investments, so they could afford to be more focused on gaining market share by cutting rates.”

These rate cuts are described in reinsurance firm Swiss Re’s information brochure A History of US Insurance as “unsustainably low”, owing to “a feeling of hubris” nurtured by the favourable investment climate.

But the chickens came home to roost, and what’s known as the “liability crisis” – a period during the early to mid-1980s in which commercial liability claims skyrocketed – coincided with falling interest rates to devastate insurance capacity.

This didn’t just impact on US insurers either, as many Lloyd’s of London syndicates in the UK wrote commercial policies in the US.

Some were wiped out completely during this period, as liability claims – those paid by insurance companies on behalf of a policyholder liable for the losses of a third party – were pumped up significantly by court decisions that favoured claimants.

“Losses started pouring in and interest rates fell, so surplus contracted, there was red ink everywhere and the market went into a tailspin,” says Zuckerman.

Fast-forward to today though, and insurers have been dealing with persistent low interest rates for more than a decade since the financial crash of 2008.

On top of this, the industry has a much more mature and data-driven understanding of risk to inform its tolerance for underwriting certain perils.

“The insurance industry is stronger today than it was in the 1980s,” says Zuckerman.

“While we have seen some coverages go away, it’s not because insurance companies are going bankrupt like they were back then.”

According to the Global Insurance Market Index – a quarterly report on commercial coverage pricing published by brokering giant Marsh – the market has been hardening since the first quarter of 2019, after a period of relatively flat rates.

It’s not all about pricing though, and like Zuckerman says, insurance companies have pulled out of certain coverage types, as well as tightening their policy language and reducing their indemnity limits on others.

The topic of what caused the hard market insurers are operating within now could be a subject for academics to toil over in the future, much like they still do over the hard market of the 1980s.

Zuckerman points to increased geopolitical tensions around the world – something that has already caused rate increases in marine coverage – as well as social inflation in the US, and the UK’s departure from the European Union, as possible causes of rate hardening.

But he, Swanke and several other industry veterans say it’s the pandemic that could shunt the industry into another seriously hard market.

How is the pandemic further hardening the market?

The current coronavirus pandemic has led to a large degree of uncertainty over business interruption coverage, with providers in the US, UK and elsewhere currently facing legal challenges over the nature of policy wording that could result in a number of insurers paying out for a risk they never intended to cover.

The SARS outbreak of 2002 to 2003 alerted the industry to the potential threat a pandemic could have, and it responded by rewriting policies to exclude unknown pathogens or limit outbreaks to a specific location up to a fixed-mile radius.

In the US, there’s another element to certain legal battles, and that’s the argument of whether or not a virus can cause physical damage, and therefore trigger a business interruption claim without the need to debate ambiguous wording.

Risk manager-turned-insurance-professor Zachary Finn, who teaches insurance and risk management at Butler University, Indiana, has first-hand experience of the nuances of property damage clauses.

“I once had $15m worth of inventory declared a total loss because the insurance company and I agreed that it was dirty, and dirty equalled property damage,” he says.

The importance of this is that certain businesses, like theatres and other public entertainment venues, have had to be sanitised in accordance with public-safety procedures, as authoritative sources have warned that the coronavirus can live on certain surfaces for a matter of days.

“If this or that venue is shut down to be sanitised, is it dirty with the coronavirus?” Finn asks.

On top of the doctrine of reasonable expectations – a legal principle in contract law that dictates insurance policies should be interpreted according to the understanding of a reasonable person who is without expert knowledge – Finn’s question raises another potential barrier insurers may have to overcome in court.

NS Insurance previously discussed the potential for legal disputes with former claims attorney and current RiskGenius CEO Chris Cheatham, who added to these concerns that legislation at the state level could influence court decisions.

Some states have even gone as far as proposing laws that would retroactively include Covid-19 and pandemics in policies, despite insurers having written exclusions for viral risk, or where they do cover it, having a list of included diseases.

Back in May, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago estimated that the number of policies which could be affected by this legislation comprised roughly 20% of total US commercial property premiums.

Since then, resistance from the industry over potential laws, which it argues would threaten the solvency of insurers, has led to Louisiana lawmakers shelving their proposal – but that still leaves similar laws being discussed in New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Faced with all of this uncertainty, insurance companies have already acted to reduce their exposure to Covid-19 by tightening the wording in their policies to directly exclude both Covid-19 and pandemics generally, as well as reducing indemnity limits and coverage availability.

The Council of Insurance Brokers and Agents (CIAB) reported that 66% of brokers in its latest survey reported that Covid-19 has affected the availability of coverage for commercial property and casualty lines, with one respondent also noting insurers were placing greater scrutiny on the underwriting of businesses considered essential.

Prices have continued to rise too, with Marsh recording a 14.4% rise in commercial premium in its Global Insurance Market Index for Q1 2020, while CIAB reported a 12% rise in commercial property premiums, and a 6.7% climb in the cost of business interruption policies.

While both organisations say these increases aren’t due to the impact of Covid-19, the CIAB also recorded a 75% jump in brokers that have experienced increased business interruption claims.

Both CIAB and Marsh expect Covid-19 to accelerate market hardening and affect the availability of coverage throughout 2020.

The pandemic could act as a catalyst for further growth in captive insurance

It’s not just Swanke at Willis Towers Watson that’s noticed an uptick in demand for the formation and management of captives; another giant in the sector, Marsh, has observed a similar jump in interest.

“Marsh is on track to probably double the amount of captives we formed last year,” says Michael Serricchio, managing director of Marsh Captive Solutions.

“The captive market before Covid-19 was already on a growth trajectory, especially because of the hardening market that started last year and continued into January.

“But then you have the perfect storm of Covid-19 and the inability for customers of insurers to make claims for non-damage business interruption on their property policies.”

According to Serricchio, the lines of risk customers are most keen on insuring with a captive, rather than through the commercial market, are property, directors and officers, errors and omissions and product liability.

“Those are the major pain points of clients from all industries, of all sizes and all geographies,” he adds.

Depending on the line of coverage, Serricchio says rate increases have reached highs of between 100% and 1000%, which is why some businesses are looking at either forming a new captive or expanding an existing one.

“Those increases are not common, and they’ve not been budgeted for in these tough economic times,” he adds.

Serricchio believes early court decisions regarding business interruption disputes over Covid-19 may have a compounding effect on the growth of captives too.

For many disputes, it’s too early to tell how many decisions will favour insurance companies, but in one recent case in New York, that’s exactly what happened.

In Social Life Magazine Inc v Sentinel Insurance Co, the magazine publisher had sought a preliminary injunction – an expedited ruling that would require the defendant-insurer to pay the company’s business interruption claim if the case was resolved in the plaintiff’s favour.

But presiding judge Valerie Caproni denied the publisher’s argument, giving its legal counsel “an ‘A’ for effort” and “a gold star for creativity”, but deciding “this is just not what’s covered under these insurance policies.”

Whether the upward growth trajectory of captive formations would have continued at the same level without the pandemic isn’t a settled issue for Serricchio.

“Every day I have a conversation with a new or existing client that’s struggling with the pains of those four lines I mentioned,” he says.

“You’re not seeing this huge growth just because of the pandemic. You would have seen it without and perhaps even more so, because companies would have more cash so they’d be less fearful about setting up a captive.”

Despite this, Serricchio does believe the pandemic has given companies a new reason to form a captive, especially when there’s potential for a government backstop to make future losses more manageable.

How would a government backstop affect the captive marketplace?

In the US, there are currently three major plans under consideration in Congress that would use varying amounts of government money to absorb the losses of a future pandemic, allowing coverage to be priced in a way that’s both affordable for consumers and sustainable for the insurance industry.

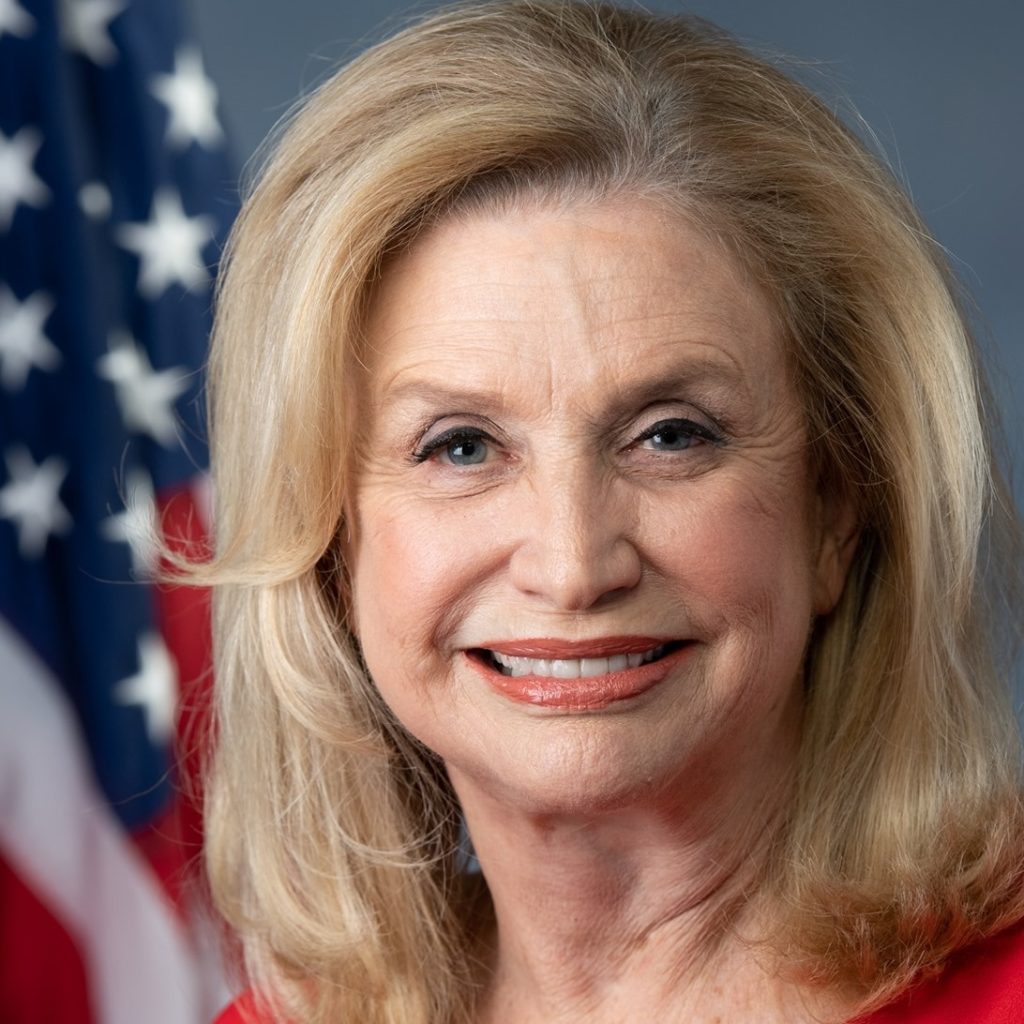

Chubb was the most recent to throw its hat in the ring with its Pandemic Business Interruption Program, with New York Congresswoman Carolyn B Maloney’s Pandemic Risk Insurance Act (PRIA) in the early stages of discussion while a handful of industry groups are attempting to derail it with their own Business Continuity Protection Program (BCPP).

But Swanke isn’t convinced that a backstop for losses will be the government’s answer to pandemics this time.

“My instincts tell me we’re not going to see government solutions like we saw after 9/11 with terrorism risk.

“I don’t think companies ought to be holding their breath, instead they need to grab the bull by the horns and develop their own risk-financing programmes to encompass those types of risks.”

Zuckerman is on the same page as Swanke regarding the need to be proactive, but he goes even further to suggest that a backstop may not only be unlikely, but potentially undesirable, because it could lead to complacency.

“If you tell me that PRIA is going to drive better residual risk management then I’m on board – but I’m not convinced it will,” he says.

“The insurance market will be happy to sell [pandemic coverage] with a backstop, and then the country will get complacent.

“We need to hold people’s feet to the fire. If they have the energy to form a business, and the intelligence to manage risk, we just need to open their eyes to how to do it properly.

“If we do that, we don’t need government backstops.”

Although Zuckerman believes a backstop for pandemic losses will “probably dampen” the growth some expect to be spurred on by the need to protect against the next big outbreak, he says those that look to take a more long-term, less reactive approach to their residual risk, will just use whatever backstop is created to mitigate their losses.

Serricchio, on the other hand, sees pandemic risk as a potential driver of captive activity, so much so that he’s been working within Marsh to design a pandemic insurance proposal that’s palatable to reinsurers.

“What I’ve been specialising in over the last three months is a Pandemic Re policy, where there’s a captive writing the policy limit and various reinsurers come over the top to take some of the risk and limit the captive’s net retention,” he says.

The challenge, he adds, is that just like cyber risk 10 or 15 years ago, there’s an education process needed for both reinsurers and organisations like Marsh to effectively model the risk and establish the right triggers – a process that’s made much easier when the data isn’t as scarce as it is for a one-in-100-year occurrence such as a pandemic.

Serricchio also believes a backstop provides even more reason for captives to form or take on pandemic risk in their existing risk-retention framework.

“It’s going to make them more feasible for different sized companies,” he says.

“Large companies will self insure at a very high retention rate for pandemic BI (business interruption).

“Then you’ll have the larger middle-market organisations setting up captives to take advantage of PRIA, which in my opinion would be a good idea.”

In its current iteration, PRIA includes captives in its definition of insurance companies able to engage with the programme, and although the plan’s current insurer excess, calculated as 5% of the previous tax year’s gross earned premium, will result in smaller individual contributions from captives, Serricchio says the aggregate total could still result in a big enough pool to make PRIA viable.

“The excess piece in PRIA will largely come from insurance companies, but some captives taking advantage of the programme will have large premium bases,” he adds.

“Marsh’s captive book has about $61bn worth of premium.

“That’s more than Allianz’s property and casualty book, and that’s the largest insurance company in the world.”

To what extent will the commercial insurance market lose out if more companies self-insure using captives?

As a simple mathematical calculation, more risk being insured in captives means less premium collected by insurance companies, unless they’re able to participate at the reinsurance level.

For Serricchio, the preferable economics of using a captive to prepare for the next pandemic over reliance on the commercial market are undeniable.

“If there’s not a pandemic for the next 10 years, you’ve thrown away 10 years of premium,” he says of using market coverage.

Instead, he advocates setting up a captive with a low retention of risk and a low indemnity limit for pandemic losses, which he says will allow the pool to grow over time, aided by investment gains.

This way, if PRIA is passed, that excess accounting for 5% of gross earned premium will be “more palatable”, and if a backstop does lead to affordable coverage in the commercial market, they can cover any remaining exposure by buying it there.

Swanke calls this “arbitraging the marketplace”, a term he explains as “using captives as a tool” to get the best value out of a hard or soft market.

With the hard market expected to continue for years, not months, it’s not just single-parent captives – the most common type – he and Serricchio expect to be used to arbitrage the market, either.

In the hard market of the 1980s, faced with no affordable option to indemnify themselves against commercial liability losses, smaller organisations without the balance sheet to establish a single-parent captive joined together to carry each other’s risk.

According to Swanke, history is beginning to repeat itself.

“As this market hardens, we’re seeing smaller to medium-sized companies come to us and say ‘can you help us explore whether or not a group captive makes sense?'”

This isn’t a decision firms make lightly, however, because the need for a homogenous risk profile undoubtedly leads to “fierce competitors” carrying each other’s risk.

“They become strange bedfellows when they band together to get relief from a hard market, but if conditions get bad enough, even the fiercest of competitors will group together for premium relief,” Swanke adds.

Neither Swanke or Serricchio see insurance as a zero-sum game, after all, both Marsh and Willis Towers Watson have branches that broker insurance contracts with industry underwriters, and a hard market makes that more difficult.

But both believe the conditions of the hard market, made worse by the pandemic, have forced the hands of companies looking to manage risk efficiently.

“They’re forcing our clients to think about a captive or just very large self-insurance,” says Serricchio.

“That insurance industry isn’t worried about captives, just like they haven’t been for the last 20 or 30 years, but I think we’re going to see some big companies taking very bold measures and not using insurance as much as they did in the past.

“If they’re using their own balance sheets in a captive instead, that’s going to affect insurers and drive negotiations with them as well.”

Swanke sees captives as an even greater threat to the insurance industry’s market share, and it’s because of the way he witnessed the last hard market end.

“Every time we go into one of these hard markets and come out, there’s another chunk of the commercial insurance marketplace that is lost for good,” he says.

“Some of the group captives have even turned into full-blown insurance companies.”

He uses the example of United Educators, a captive Willis Towers Watson put together in the 1980s that is legally still a risk-retention group (RRG), but now acts like an insurance company by selling coverage to US educational institutions.

The potential for insurers to lose market share doesn’t stop there either, as Swanke agrees with comments made by Butler University’s Finn, who believes companies like Amazon will recognise the favourable economics of using captives to sell coverage that complements their business model.

“I think it’s gonna happen and that’s what we’re evolving towards,” he says.

“They could even have a fronting company issue a policy and then reinsure it into their own captive, so they don’t even need to set up a commercial insurance company – you can bet they’re thinking about it.”

Zuckerman says Apple already retains a degree of the risk from its warranty policies in its own captive, and points to other examples of firms using their captives to sell coverage to third parties.

“If bigger organisations with single-parent captives that really know how to manage reinsurance placement start selling third party coverage to their important stakeholders, the commercial insurance industry will lose significant market share forever.”